Estevan Oriol is no ordinary photographer. His humble beginnings in music, hard-work ethic, and unmatched integrity set him apart from others and allowed him opportunities that most might never dream of. Thirty years later, he’s become a master of his craft while working with legendary figures such as Snoop Dogg, Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, and so many others in the music and film industries.

In this interview, we’ll dig deep with an amazing artist who has truly pushed through boundaries to become who many believe is the best music and street photographer on the planet today.

How did you begin your career in music?

Well, I was friends with DJ Muggs back in ‘89. I met him from working the doors of a lot of the clubs in LA, I was a doorman handling the VIP lists. I met a lot of bands that way. It was a lot different scene than it is today. Back then, it was kind of like a family. You’d even be like, “Okay, man. I’ll see you Thursday night at this club.” So, people were a lot cooler back then—they were a lot more in tune with each other.

In ’92, Muggs was like, “Hey, I’m putting out this new group and I want to have you work for us.” And I was like, “Cool.” Because I had already been to a couple shows with Cypress Hill, so I thought he was going to hook me up with a job with them. And he goes, “It’s for these new white boys that are going to be rapping.” And at that time, there was 3rd Bass and Vanilla Ice, so I was like, “Man, which one is it going to be? I’m hoping it’s more of the 3rd Bass style than Vanilla Ice.” He goes, “You know, it’s our homie Everlast.” And I go, “Oh, okay cool.” He then proceeds to drop the name House of Pain and he played “Jump Around” for me. I was like, “Oh, shit.” You could tell instantly that was a hit.

That is how it all started. Once I got in touch with them, I was hired as their tour manager and ended up going out with them on the promo tours, on the college tours, and stuff like that. That’s what we called working a record back then. It was a way different scene, and I was just getting my expenses paid for including flights, hotel rooms, and food money, etc. The guys would take $300 bucks each show and give me $100 bucks. So, sometimes we’d do two, three shows in a day. You do a couple shows a week, and you’re doing pretty good. So, I was like, “Man. This is a cool thing. It’s paying off.”

Shortly thereafter, we went on tour with the Beastie Boys and we got kicked off of that tour because the tour manager of the Beasties gave us tickets for Everlast’s mom in the grass area at the arena (which is the farthest away you could be from the stage). Everlast felt disrespected that the guy just gave us the worst seats in the house for our guests. He just kind of blew up on the guy and gave him a piece of his mind. The next day we were kicked off that tour and that happened to be a blessing in disguise.

From that point forward, I went from managing the basics to running the entire back end including overseeing travel, merchandise, security, and even the full-blown accounting process. I guess you could say I did a little bit of everything.

I was with House of Pain from ’92 to ’94. At that time, they decided to break up, and I told the guys from Cypress Hill, “Hey, these dudes are breaking up, so looks like my tour managing days are numbered.” And they go, “No, no. We got a spot for you over here because our tour manager’s acting up, so we’ll just move you right over to here.” And that’s what happened. I began managing Cypress Hill from 1994 to 2005, all the while I was taking photos. In ’97, I started filming them in 8-millimeter with a video camera and got into directing music videos simultaneously. I also had a clothing company while doing my photography, directing videos, and tour managing (all at the same time).

Wow, what a dream. Seems like it came fairly easy to you.

It was a lot of hard work. A lot of guys from the crew that came in before me (and after me) failed to take on the opportunity that was right in front of them. They just wanted to travel with the band and live the rockstar lifestyle without doing any of the work. But me, I was always taught to work hard, and just try to outshine everybody at your job without being one of those people that are like, “Oh, look at me, I’m doing my job better than he is.” You know, kind of dry snitching your fellow workers out.

Me, I just did the work, and if they notice it, cool. If they didn’t, they didn’t. But at least I knew I was doing my thing. They were able to see that, and they were like, “Hey, bro. You’re kicking ass, so you need a raise, and we want you to do more.” And just took off from there. The more work I got, the more I was rewarded. I ended up hustling the photography and the video thing side by side. Around 2005 they were kind of burned out on touring, so I just dove in headfirst to that stuff, and it took off.

Help our readers understand your unique style of street and music photography.

I say my is style is rough, rugged, and raw. And the way it came to be is, I was an insider. I was part of the band, I was part of the culture, I was part of hip-hop way before I became a tour manager. I was working at those clubs. Before that, I was into the break-dancing scene and stuff like that. Heck, I was listening to hip-hop in the early ’80s here in LA when it all first started.

I bought my car in 1989 and started lowriding. I didn’t have a camera until the early ’90s. So, I was already lowriding before I was taking pictures of it all. And I was already touring with the band before I was taking pictures. I was part of the lifestyle and culture and I always had a camera with me. I just was clicking away here and there, little by little. I saw that I had something that others didn’t when they were taking the same photos, and I just pushed it. I also had a couple people in my corner telling me, “Hey, you know you got something here. You should really follow it.” And that’s what I did…

Anyone in particular influence your style?

My dad influenced me a lot. He was an amazing photographer. There were also many others of course. I would look at photos in Time or Life magazine and I was particularly driven to the black and white ones and also photographers like Mary Ellen Mark and Daido Moriyama. I saw those photos and I was like, “That’s the level I want to be on some day. But I don’t want to copy their style or do what they do.” So, I did my own thing, and worked as hard as I could to get there.

Mark Machado, aka Mister Cartoon, and you go way back. How did that relationship begin and why has it remained so strong all of these years?

It all began when I met him at a record release party for Penthouse Players. I was with my friend Donny Charles. At that time, he was a manager of WC and the Maad Circle which ultimately became the Westside Connection. He was also into low riding as well and ran a record label called Hood Rat Records. When we walked in there, he was like, “Hey, there’s my boy Cartoon. He lowrides too and he’s also in the music industry. I want to introduce you to him.” So, I went over there, met Cartoon, and we clicked up really good. We finally connected and then ended up meeting up shortly thereafter. He was going to Japan, and I had just come back from Japan, so I was telling him a little bit inside scoop.

And when he came back, he called me up, he was like, “Hey man, that shit was dope. That was a trip.” And I go, “Yeah.” And then we shared stories on Japan, and then we began hanging out. We ended up clicking about everything, lowriding, music, working in the hip-hop world, and ended up talking about things we could collaborate on including brainstorming ideas for different types of projects. It just went from there. There was no big game plan or anything like that, it just unfolded naturally, organically.

Was there one project in particular that stood out to you as one of your favorites in collaboration with him?

I would say probably say the Righteous Kill movie back in 2008 because we were both big fans of De Niro and Pacino. We always talked about that as far as our love for their movies and how they went about their careers. And we finally got the chance to work with them on a spec project because they had already shot the initial movie poster. They just wanted Cartoon to draw a skateboard for Rob Dyrdek, and I was going to be doing some alternative marketing for the movie. We ended up doing the spec job with another poster, and I went and shot Al Pacino and Robert De Niro. Cartoon did the logo and our friend Patrick Martinez did the layout. It ended up being the campaign for the movie worldwide, including the DVD cover. So, to be able to work with your best friend and your business partner on a project that included people that you’ve looked up to all your life was a pretty cool and standout project.

How did you both decide to pull your unique history together into the critically acclaimed Netflix documentary, LA Originals?

Well, I was always filming and shooting everything we worked on. In the early 2000s, I felt like I had a pretty decent amount of work in including video footage and photos. We then began shopping the documentary and signed up with Brian Grazer. The deal was, we were going to do a feature with him, and the documentary was going to be on hold until that was done and gone.

So, we did seven years of script writing on that, and then he dropped that idea and ended up going with another. Grazer was like, “Hey, you know our contract’s up, but I still want to work with you guys on a movie I’m doing called Lowriders. I want you both executive produce and consult on the project.” We did that, and then right after that was over, we were able to put out the original documentary because we had a noncompete contract with him that finally expired.

After 10 years, we got our footage back and then I met Sebastian Ortega, a TV executive in Argentina. He was like, “Hey man, I’ve been a big fan of yours since day one. What happened to that documentary?” I said, “We still got it. We just got all the rights back.” He ended up flying me down to Buenos Aires and introduced me to his crew down there. He’s like, “You’re in good hands. My people know what they’re doing. Let’s make this thing pop.” And that’s what he did. Sebastian already had existing shows on Netflix, so he went into Netflix with the documentary, and it was originally only supposed to be for Latin America. However, they must have liked it because when the Latin Netflix showed it to the execs at US headquarters over here, and they also liked it. We were able to release it worldwide.

As our publication focuses on all-things vinyl, I’d love to get your take on the sound of old school vinyl vs. current digital formats. Is there a difference?

A thousand percent. It’s not as clear, and you get to hear the crackles in the music throughout the record along with natural things that just happen. There might be a group that makes this distinct sound, like the needles dragging over the vinyl and it hits a little bump. It sounds weird, but it’s an imperfection and it’s cool. It’s something that gives it that old school vibe that you don’t get with digital stuff.

To me, I relate it all to analog. Like film, it’s all something you can touch. To me, vinyl and analog music is just like film in video or stills. So, I’m an old school kind of guy, I like that stuff. I still play records; I got a big vinyl collection. I used to go vinyl shopping all the time with DJ Lethal from House of Pain when we were touring.

Any interesting stories on the vinyl trail from back in the day?

I remember this one time Lethal and I went out shopping. I would always buy old soul and hip-hop shit with him. And then later on, I started working with Cypress and I was going out with Muggs. It would be me, Muggs, and Alchemist going to record shops in all of these little cities. We’d pull into these towns (many with record shop upstairs), and we were buying boxes of records. And then the guy would be like, “Hey, you guys want to see some more? I got some more in the basement.”

And they’d let us go in the basement where there were boxes upon boxes of vinyl. Nobody had been in there for years except the guys at the store. So, we’d end up buying 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 boxes of records and then have to take them in the cab and then putting them underneath the bus. We’d carry them all tour long, and then those guys would take them home, chop them up, and make hits out of em’.

What are some of your favorites from that collection?

Well, like I said, I like a lot of old soul, old hip-hop, the stuff they don’t make anymore. I also like classic rock. I have a lot of Led Zeppelin records and a collection called East Side Oldies. Heck, I even have some limited edition ’70s R&B and soul. I never really got into the 45s too much, but I appreciate those guys that collect all the 45s soul music. I think that’s pretty dope. But for me, I love the albums.

Digital or film?

I’m shooting film unless I’m forced to shoot digital. You almost have to put a gun to my head to shoot digital or be putting money in my pocket.

Canon or Nikon gear?

Canon.

Prime lenses or Zoom lenses?

I prefer primes. I have 28, 35, and 50 on my Canon E1. But if I’m doing a filming situation with my Canon 5D or my Black Magic, I’ll use the zooms with that because you’re trying to capture so much in so little time. When you’re filming something, you’re doing the wide shot, the medium shot, and the close ups back to back. In those cases, I have a 24—70 and a 70—200. Those are my zoom lenses.

Soundboard shooting or pit shooting?

I like doing the pit and the side of the stage.

LA eateries: El Cholo or El Tepeyac Café?

El Tepeyac.

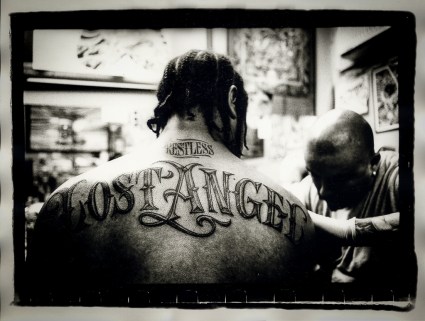

Your photos: LA Fingers or Rascal?

My photo of LA Fingers changed my life. That photo is untouchable. I think my photo of Rascal is also great shot, a capture of LA as far as the whole culture captured in one photo.

Your books: LA Woman or This is Los Angeles?

I would say I have to go with This is Los Angeles because it has a bigger variety of the genres I shoot.

Your videos: Cyprus Hill’s “Dr. Greenthumb” or Tech N9ne’s “Like Yeah”?

I would say Dr. Greenthumb. I think I really got more creative and out of my comfort zone because the song’s about weed and we couldn’t show weed at that time. I created that character for the video and Be Real still uses it for everything he does today.

Estevan Oriol Official | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter

ALL PHOTOS: ESTEVAN ORIOL